Speaking of Bioethics… By Thomas G. Lederer, M.A.

A collection of thoughts, excerpts, ramblings, streams of consciousness…

Ethics Committee Handbook —For New Members Orientation

Center for Practical Bioethics-Kansas City, Missouri

Reviewed and Revised February 2018

In conclusion, ethics committees continue to have a pivotal role in the provision of good healthcare. Perhaps their greatest role is to ask the right questions throughout every tier of the institution, and the question that grounds all the others is this: “For whom shall we care?” On the answer to that question hangs an elegant and fitting response.

End of Life Discussion in the Film “Fletch”

Dr. Joseph Dolan: You know, it’s a shame about Ed.

Fletch: Oh, it was. Yeah, it was really a shame. To go so suddenly like that.

Dr. Joseph Dolan: Ahh, he was dying for years.

Fletch: Sure, but… the end was really… very sudden.

Dr. Joseph Dolan: He was in intensive care for eight weeks!

Fletch: Yeah, but I mean the very end, when he actually died. That was extremely sudden.

What is Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act?

The Oregon Health Authority

The Death with Dignity Act (the Act) allows terminally-ill Oregonians to end their lives through the voluntary self-administration of lethal medications, expressly prescribed by a physician for that purpose.

The Act was a citizens’ initiative passed twice by Oregon voters. The first time was in a general election in November 1994 when it passed by a margin of 51% to 49%. An injunction delayed implementation of the Act until it was lifted on October 27, 1997. In November 1997, a measure was placed on the general election ballot to repeal the Act. Voters chose to retain the Act by a margin of 60% to 40%.

There is no state “program” for participation in the Act. People do not “make application” to the State of Oregon or the Oregon Health Authority. It is up to qualified patients and licensed physicians to implement the Act on an individual basis. The Act requires the Oregon Health Authority to collect information about patients who participate each year and to issue an annual report.

Can’t we Talk About Something More Pleasant?

By Roz Chast

Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch and his views on physician assisted suicide…

“All human beings are intrinsically valuable,” Judge Gorsuch wrote in his the book in 2006 prior to his taking a seat on the Supreme Court, “and the intentional taking of human life by private persons is always wrong.”

He continues, “We seek to protect and preserve life for life’s own sake in everything from our most fundamental laws of homicide to our road traffic regulations to our largest governmental programs for health and social security. We have all witnessed, as well, family, friends, or medical workers who have chosen to provide years of loving care to persons who may suffer from Alzheimer’s or other debilitating illnesses precisely because they are human persons, not because doing so instrumentally advances some other hidden objective. This is not to say that all persons would always make a similar choice, but the fact that some people have made such a choice is some evidence that life itself is a basic good.”

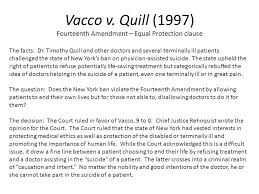

The American Civil Liberties Union stated in its Oct. 1996 amicus brief in Vacco v. Quill that:

“The right of a competent, terminally ill person to avoid excruciating pain and embrace a timely and dignified death bears the sanction of history and is implicit in the concept of ordered liberty…A state’s categorical ban on physician assistance to suicide — as applied to competent, terminally ill patients who wish to avoid unendurable pain and hasten inevitable death — substantially interferes with this protected liberty interest and cannot be sustained.”

Scott Peck, MD “Denial of the Soul—Spiritual and Medical Perspectives on Euthanasia and Mortality” © 1997

“Given the medical armamentarium available to adequately relieve physical pain, the improving climate in regard to full use of that armamentarium, and the option for those with terminal diseases to switch from hospital to hospice care, there is no reason for anyone to die with intractable suffering. Regardless of what is causing your pain, your health care providers can likely relieve it.”

PAIN, HURT, AND HARM:

THE ETHICS OF PAIN CONTROL IN

INFANTS AND CHILDREN (1994)

Gary A. Walco, Robert C. Cassidy, Neil L. Schechter

“The ethical responsibility of clinicians is to provide full treatment of pain in children unless otherwise justified by defined therapeutic benefits. Three specific tests should be applied. First, is the pain useful? Is it the means to achieving an important goal? Second, is the pain necessary? Are there other, less hurtful means of achieving that goal? Third, is the pain at the lowest possible level? If there is a therapeutic benefit from a child’s pain, one must be exquisitely economical with it.”

Relief of Physical Pain and Depression

“A Pastoral Letter on Care for the Dying and Sick”

The Diocese of Rockville Centre, Bishop John McGann, et. al. (1997)

“A number of studies show that when it occurs, the desire for death among terminally ill patients is “closely associated with depression, and that pain and lack of social support are contributing factors.” Studies also show that people stop asking for help to die when their pain and depression are adequately managed and other symptoms are controlled. When someone is suffering, the answer is not to kill the sufferer but to relieve the suffering.”

Excerpt from “Welcome to the Monkey House,” by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

“There was a Howard Johnson’s next to every Ethical Suicide Parlor, and vice versa. The Howard Johnson’s had an orange roof and the Suicide Parlor had a purple roof, but they were both the Government. Practically everything was the Government…In a really good week, say the one before Christmas, they might put sixty people to sleep. It was done with a hypodermic syringe.”

Strict limits on opioid prescribing risk the ‘inhumane treatment’ of pain patients

By STEFAN G. KERTESZ and ADAM J. GORDON FEBRUARY 24, 2017

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services are going to enforce hard limits on opioid dosing is a dangerous case in point. There’s no doubt that we needed to curtail the opioid supply. The decade of 2001-2011 saw a pattern of increasing prescriptions for these drugs, often without attention to risks of overdose or addiction. Some patients developed addictions to them; estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention range from 0.7 percent to 6 percent. Worse, opioid pills became ubiquitous in communities across the country, spread through sale, theft, and sharing with others, notably with young adults.

- First, it reflects a myopic misunderstanding of addiction’s causes, one at odds with a landmark report issued by the US surgeon general in November 2016…

- Second, we have alternatives to bureaucratic controls…

- Third and most troubling is the increasingly inhumane treatment of patients with chronic pain. Fearing investigation or sanction, physicians caring for patients on long-term opioids face a dire choice: to involuntarily terminate prescriptions for patients who are otherwise stable, or to carry on as embattled, unprotected professionals, subject to bureaucratic muscle and public shaming from every direction.

The other opioid crisis: pain patients who can’t access the medicine we need

By Anne Fuqua March 9, 2018

Anne Fuqua is a former nurse living in Birmingham, Ala.

“As a former nurse, I never dreamed that our government would encroach to this degree on the relationship patients have with their medical providers. Twenty years ago, when I was attending nursing school, the Joint Commission, a healthcare accreditation board introduced the “fifth vital sign,” which required health-care providers to ask patients whether they had pain and how severe it was as part of the routine assessment of vital signs. Now we’ve done an about-face because of opioid abuse to implement policies that will cause physicians to abandon patients or taper medications regardless of whether this will harm their quality of life.”

The Real Down Syndrome Problem

By George Will

“About 750 British Down Syndrome babies are born each year, but 90 percent of women who learn that their child will have — actually, that their child does have — Down syndrome have an abortion. In Denmark the elimination rate is 98 percent… It speaks volumes about today’s moral confusions that this — the disruption of an unethical complacency — is the real “Down syndrome problem.”

About 750 British Down Syndrome babies are born each year, but 90 percent of women who learn that their child will have — actually, that their child does have — Down syndrome have an abortion. In Denmark the elimination rate is 98 percent… It speaks volumes about today’s moral confusions that this — the disruption of an unethical complacency — is the real “Down syndrome problem.”

The Principle of Double Effect

The AMA Journal of Ethics

The history of the principle of double effect dates at least as far back as the work of St. Thomas Aquinas. Although St. Thomas did not use the term “double effect” or refer to the principle, he used the concept in justifying killing in self-defense [1]. In so doing, he recognized the bad effect (death of the assailant) and the good effect (preservation of the victim’s life). Can one justifiably kill an attacker to save his or her life? St. Thomas answered in the affirmative. Likewise those who use the principle of double effect today attempt to discern the rightness or wrongness of actions that will have both good and bad (evil) effects.

To make such a determination, one must analyze an action on the basis of four conditions; all of which must be met for the action to be morally justifiable. The conditions of the principle of double effect are the following [2]:

- The act-in-itself cannot be morally wrong or intrinsically evil [3].

- The bad effect cannot cause the good effect.

- The agent cannot intend the bad effect.

- The bad effect cannot outweigh the good effect; there is a proportionate reason to tolerate the bad effect.

New York State Department of Health

Does the MOLST form replace traditional Advance Directives?

No. A properly completed MOLST form contains legal and valid medical orders. It is not intended to replace traditional advance directives like the health care proxy and living will.

How can the pinkness of the MOLST form be maintained?

When the patient is transferred between care settings, a copy of the form should be made on Pulsar Pink paper. The original MOLST form should accompany the patient and be placed in the chart in the new care setting or placed on the refrigerator at home.

Respecting Patient Wishes, Family Intentions

Thoughts from an Unidentified Huntington Hospital Department Head

(NB: Paraphrased from an extensive conversation in 2017.)

“It is extremely difficult in many cases for a doctor to step back and stay relatively neutral when life-or-death decisions must be made at bedside. Patients and their family are often medically uninformed, often resistant or incapable of grasping the nature of the illness or the implications of the options. Patients may seem to be ready to give up, yet that impression may be impacted by depression, confusion, and/or by medication.

“Families are rarely medically neutral but are often influenced by sadness or exhaustion brought about by having had to care for their loved one or seeing them in what they deem to be a state of suffering. Similar to a common theme often heard at a wake is “He (she) is in a better place,” decisions about further medical interventions can be influenced by such emotional or spiritual perceptions.

“Still further–hopefully at a minimum–family members are influenced by finances, perhaps by the fact that additional care and necessary help thereafter may push families far beyond their budgets. And, regrettably, there are sibling rivalries which extend into adulthood. Not only can they impede familial communication and decision-making but medical decisions can be made with inheritances in mind.”

Study Says Euthanizing More Patients Will Save the Government Money

By Alex Schadenberg January 24, 2017

Ottawa, Canada January 24, 2017

The researchers found that the Canadian healthcare system will save between 34.7 and 138.8 million dollars per year, depending on the number of euthanasia deaths. Canada has a universal healthcare system, whereby the financial cost for healthcare is primarily covered by the government.

The cost savings were assessed based on a Netherlands study estimating the number weeks that lives were shortening by euthanasia, multiplied by the average cost of care for a person nearing death, and multiplied by the likely number of euthanasia deaths in Canada. The study also considered the cost of the euthanasia procedure and potential variable costs related to patients using palliative care.

Palliative Care and Pain Management at the End of Life

by NetCE, Lori Alexander

Spirituality

“The need for spirituality at the end of life is heightened, and patients will search for meaning as a way to cope with emotional and existential suffering [385]. Spirituality helps patients cope with dying through hope. At the time of diagnosis, patients hope for cure, but over time, the object of hope changes and the patient may hope for enough time to achieve important goals, personal growth, reconciliation with loved ones and a peaceful death. Spirituality can also help a patient gain a sense of control, acceptance, and strength. As a result, greater spiritual well-being has been associated with decreased rates of anxiety and depression among people with advanced disease.”

“The Limitations of Our Mortality”

Pope Francis, November 7, 2017

“…And even if we know that we cannot always guarantee healing or a cure, we can and must always care for the living, without ourselves shorting their lives, but also without futilely resisting their death. This approach is reflected in palliative care, which is proving to be of most importance in our culture, as it opposes what makes death most terrifying and unwelcome—pain and loneliness.”

When the Patient Won’t Ever Get Better

By Daniela J. Lamas, M.D., New York Times

In the early moments of critical illness, the choices seem relatively simple, the stakes high – you live or you die. But the chronically critically ill inhabit a kind of in-between purgatory state, all uncertainty and lingering. How do we explain this to families just as they breathe a sigh of relief that their loved one hasn’t died? Should we use the words “chronic critical illness”? Would it change any decisions if we were to do so? Here, I find that I am often at a loss.

My I.C.U. Patient Lived. Is That Enough?

By Daniela J. Lamas, M.D., New York Times

Even if I did tell her about anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress, I doubted that she would have been able to hear it then, through her exhaustion and pure relief that her husband would not die there in that room. I would invite him to an upcoming support group, I thought, and jotted down his name so that I would remember to do so.

Then I turned my focus from the future back to the present. He was getting better, that much was true. And for the moment, that was enough.

Donald Wilson

By Thomas G. Lederer

“I greatly appreciate your coming to spend time with me today,” said Donald Wilson, 80-year old long-time employee of our auto dealership. It was December, 2015, with just a few weeks before Christmas. He had been hospitalized for about a week after contracting pneumonia. For the prior ten months, Donald had been battling prostate cancer. He had fought valiantly with no sign of giving up or giving in.

Mr. Wilson was born on the island of Kingston, Jamaica in the British West Indies. He attended the Alpha Industrial School for Boys under the auspices of the Sisters of Mercy. Very much involved in sports as a child, he was scouted by the Boston Red Sox and signed to a contract to play for the Grandy Red Sox in Grandy, Quebec. He went on to pitch for the famous Indianapolis Clowns and the New York Black Yankees.

While playing baseball in Canada he was introduced to ice hockey and, back in the 1950’s witnessed what was at the time, unique: women playing on ice. Fast forward 60 years, Donald was obsessed with starting a woman’s professional hockey league, patenting the concept, reaching out for support from a diverse group of potential investors to include Sam Walton and Vladimir Putin.

I got to know Donald at the tail end of his career as handyman for our auto group. There was no assignment too big or too small or too convoluted for Don. He would tear down walls and midnight and have new ones up by dawn. He would risk his life to defend an employee or make life easier for others. He broke bones while pushing a bit too hard but never complained, always asked, “What’s next?”

Donald married late in life and his much younger wife who had emigrated from China had delivered the couple a young baby boy when Don was 70.

As I was about to end my visit with Donald at that south shore Long Island hospital, a nurse manager pulled me aside. She asked my relationship with him and I told her I was the human resource director at his workplace. She said that everyone on the floor loved Don and expressed concerns about his insistence that he continue treatment.

“This man’s body is being ravaged by metastasized tumors,” she said to me in confidence. “Someone close to him needs to tell him that it makes no sense to continue treatment. He should be made as comfortable as possible and accept his fate. Hospice should be considered at this point.

I never had that conversation with Donald because, much as he did everything in life, he made up his mind and found a way to do it. Upon his release from the hospital he began seeing a woman oncologist in Bay Shore who told him about new experimental drug, Xofigo. So radiologically powerful was this drug that Don was cautioned not to even come in contact with his own urine, lest he get burned.

More than two and a half years have passed since the nurse manager shared her concerns with me about Donald futile attempts to stay alive, he is in remission, driving his 2015 Chevy Equinox to Shoprite and to his son’s lacrosse games, and still working hard at establishing the International Women’s Professional Ice Hockey League.

“If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face?”

By Alan Alda

Once Helen Riess–Associate Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School–realized she had been missing her patient’s emotional ups and downs, the experience change the way she related to patients, and it changed the way she trained other doctors to care for their patients.

The first thing she had to do, she told me, was help doctors understand that, in fact, it is actually possible to learn to become more empathetic. She maintains that it’s not something you either have or you don’t. Rather, most of us come equipped with the mental hardware for it.

She told me, “I introduce them to the neuroscience of empathy”—in other words, she teaches them how our brains are wired to receive the thought and feelings of others.”

TGL 2017-2018